I must start this post immediately with a startling find—a 25-second clip of "Odissi" dance from

Lalita (1949), the second Odia-language film ever made. Odissi dance as we know it today was not even formed yet in 1949! It would be years before the dance form became known outside of its regional borders, into the late 1950s before it started to become codified into its modern design and format through the Jayantika project, and into the 1960s before it flowered and was fully recognized as one of India's classical dance forms. Take a look at this gem:

Start 1:35

While the clip is short and hastily edited, the full scene appears to be set inside an Odishan temple where rituals and dances for Lord Jagannath are being performed. The dancer, presumably meant to be a mahari (Odishan devadasi), appears and after prostrating herself before the Lord she settles into one of the elemental postures of Odissi dance, the Chauk. A jump cup reveals the dancer rotating one of her hands in the characteristic Odissi hand gesture “hamsasya.” Fascinating evidence of these dance elements from 1949.

![]()

![]()

As elaborated upon further on in this post, in 1940s Odisha brief and simple dance presentations of varying inspirations were increasing in popularity in the new professional theaters, and young girls from privileged backgrounds began learning and performing dance amidst the awakening cultural scene in Cuttack. The dance above was filmed in the latter part of the decade when the beginnings of what we know as Odissi movement vocabulary today was gaining ground in the collaborative atmosphere of professional theater.

![]() |

Mahari Suhasini, 1958 - Source:

Central Sangeet Natak Akademi |

While it's important to recognize that the dance above is a "film dance" and its intentions in presentation authenticity are unknown, it's intriguing to analyze the brief portrayal and try to make inferences from it. The dancer's appearance seems to have more affinity with other film dances of the period which took on their own style from various sources of the day. Compare the costume and jewelry of the film dancer with the picture of the Jagannath temple Mahari on the right (taken in 1958). The film dancer's blouse is not velvet (as was customary for Maharis) but rather sateen, and her jewelry-lined ears and decorated side bun seem unusual. The velveteen belt with the long frontispiece reminds me of Manipuri costume (especially Sadhona Bose's

costume in her so-called Manipuri dances in

Raj Nartaki), and the artistic design is similar to that worn by Kelucharan Mohapatra and Laxmipriya in a photo of their 1947 Dashavatara performance (see in history section below). The film dancer's appearance also seems to differ significantly from the pictures of Priyambada Mohanty in her dance costumes in the 1940s and 50s some of which are shown below.

The biggest mystery of the film dance is the identity of the dancer. I suspect she was either involved with professional theater at the time or was one of the few young women from outside the tradition learning dance. Surely someone out there knows who she is...

Note: While many varied spellings abound due to the

difficulty in transliterating the r/d sound, as of 2011 the

official spelling by law is Odisha (not Orissa) and Odia (not Oriya). Likewise, Odissi seems to be the preference though Orissi has also been used.

Odissi Dance History

For a concise summary of the history of Odissi dance, I like this quote from Anurima Banerji's dissertation "Odissi Dance: Paratopic Performance of Gender, State, and Nation":

![]() |

| Gotipua Bandha formation |

Commonly perceived as the oldest classical dance in India, Odissi originated in the eastern state of Orissa. Presented as a traditional style in discourses of classical Indian art, Odissi is actually the modern appellation for an amalgam of Orissan forms. The earliest known evidence of Odissi’s antecedents can be traced to ancient India (around the 1st century BCE) in the dance style known as Odra-Magadhi, which constituted a form of professional entertainment, interweaving dimensions of the secular and the sacred. In the 10th century CE, dance was introduced as a devotional practice in Orissa, performed to honour the Hindu divine. This temple style [was] called mahari naach (or, the dance of the maharis, female ritual specialists). [...] Stigmatized by British imperialists and indigenous elites, allegedly for its ties to prostitution, mahari naach was forced underground in the nineteenth-century era of the British Raj. Earlier in the 16th century, with the advent of the Bhakti movement in eastern India, another lineage emerged—the gotipua tradition of young boys embodying the feminine in public dance performance. This tradition escaped colonial scrutiny and survived into the early decades of the 20th century.

By the 1930s, the dance scene in Orissa aligned with a new cultural environment. As mahari naach diminished in stature, concert dances crafted in indigenous idioms began to emerge in the context of Indian nationalism. Inspired by prominent choreographers like Uday Shankar, an innovator in modern Indian dance, and Rukmini Devi, a pioneering figure in classical Bharatanatyam, dancers in Orissa began to develop their own novel style for the stage. [...] Postcolonial architects of the dance composed a new genre, based on the principles of the ancient texts, like the Natyashastra, Abhinaya Darpanam, and Abhinay Chandrika; [...] imagery drawn from sculpture and visual art, profuse in Orissa; the rich poetic and musical repertoires of the region, especially the Geeta Govinda; syncretic religious influences, from Jainism and Shaivism, to Shakti, Bhakti, and the cult of Jagannath; the combined streams of Odra-Magadhi, gotipua and mahari naach, and Odra naach; and theatrical forms like jatra, raas-leela, and local dance drama. The reconstruction, fusion, and refinement of these congeries of forms culminated in the dance aesthetic we brand classical “Odissi” today."

As Alessandra Lopez y Royo puts it, "the real history of Odissi is more interesting and exciting than its myth of origin"—the myth of an ancient temple dance transplanted directly from the temples to the stage. As I researched Odissi's history I was fascinated to learn how what we know as Odissi today is a "superstructure crafted but [sixty] years ago, erected on the foundation of lean pickings" that largely owes its evolution to the "foothold" the dance form gained in the theater community in Odisha

22. What follows is my writeup of Odissi's past and construction as taken from the sources listed at the end of this post and in my best attempt to address inconsistencies in the data.

Most of the men who were part of the history of modern Odissi were exposed to or part of the music and dance traditions of early twentieth-century Odisha. This includes the well-known four architects of Odissi dance, Pankaj Charan Das, Kelucharan Mohapatra, Debaprasad Das, and Mayadhar Raut, as well as many other names of the period who are less remembered or nearly forgotten today. Some of the men had families attached to temple rituals and mahari dance, and most of them trained as gotipuas or were exposed to the gymnasium-like akhadas where young boys were trained in gymnastics, dance, and acrobatics.

![]() |

| Jatra in Raghurajpur - Source: [16] |

But it was the open-air,

roving drama groups who performed forms like Jatra or Ram/Ras/Krishna Leela that proved to be the most influential in shaping history. Most accounts of the four architects of Odissi dance describe their childhood fascination with these drama troupes or the local akhadas. Both

Mohan Sundardev Goswami and

Kalicharan Patnaik operated Ras Leela troupes that included Kelucharan Mohapatra and Mayadhar Raut as performers. Kalicharan Patnaik then began Orissa Theaters in 1939/40 and ushered in a revolution of modern Odishan theater with a fixed proscenium stage, complex lighting and decor, and high acting standards. Other theaters sprang up, such as Annapurna Theaters and New Theaters, and the best minds in music and dance migrated to these new opportunities. The Annapurna Theater was the first to present young girls from the theater communities on stage for dance numbers, and other theaters soon followed suit. Dance as presented in the theaters at that time was simple and stylized, "had no independent status or identity"

12 and existed simply "to embellish the dramas, often without any rhyme or reason"

13. The theater dance directors came from a wide variety of backgrounds, such as the above mentioned folk theater, akhadas, and gotipua training, but also from Chhau dance and training at Uday Shankar's institution in Almora. A popular style in Odisha at the time was "Oriental Dance" or "Adhunika Geeta" based on tribal adivasi and folk movements.

Priyambada Mohanty was among the first girls from a middle to upper-class background outside of the theater communities to learn Odissi dance. In her book on Odissi dance, she relates that in early 1940s Odisha dance was "looked down upon," seen as the exclusive domain of the touring gotipua groups patronised by zamindars, and was considered something not practiced by middle and upper-class families. Priyambada describes how dance was introduced to the circles she was part of:

"In the early 1940's, a Bengali dance teacher, Shri Banbehari Maity, from Midnapur arrived in Cuttack to make a living as a dance teacher. Little did he know that Oriya girls just did not learn dance. Of course, this was a time when love for music and specifically dance in Bengal, had been sparked by people like Uday Shankar and promoted by Gurudev Shri Rabindranath Tagore. Orissa being a neighboring state, he thought people must be interested in learning dance and therefore he came to Cuttack-the centre for cultural activities in those days. Of course, Utkal Sangeet Samaj had been started as early as 1933 and people were taking interest in teaching children music but nobody danced. My father and some of his contemporaries took pity on him and hired him as a dance teacher more to rehabilitate him than to teach their daughters dancing. This is how dance entered the aristocratic families and Maity gave lessons in about half a dozen of them."

It seems there was at least one other dance teacher giving similar lessons, and the style was a sort of general "oriental dance" of the day that borrowed from various known styles. Priyambada then started learning dance from the Odissi music doyen Singhari Shyam Sundar Kar, and her occasional short pure dance pieces became popular at schools and soon cultural events. By the late 1940s, more girls were learning what we call "Odissi" dance today and schools were holding dance competitions.

![]() |

Kelucharan Mohapatra and Laxmipriya

in Dashavatara - Source: [16] |

Among this public awakening and interest in dance, it was the

Annapurna Theater that became a key host in the formation of modern Odissi dance. In the mid-1940s, Kelucharan Mohapatra and his future wife Laxmipriya's dances choreographed by Pankaj Charan Das and Durllav Chandra Singh impressed the public and proved popular. The 1947 Dashavatara dance performed by Kelucharan and Laxmipriya in 1947 was groundbreaking with its alternating abhinaya and rhythmic dance sequences and a form that has "remained more or less unchanged even til today" in Odissi

6. Inspired by the beautiful and talented Laxmipriya, more girls from privileged backgrounds began to learn the dance form despite the negative attitudes still prevalent towards dance. Among them were some of the big names in Odissi dance—Sanjukta Mishra (later Panigrahi, and the first girl to pursue Odissi as a lifelong career), Minati Das (later Mishra), Jayanti Ghosh, and KumKum Das (later Mohanty).

Into the 1950s Odissi began to expand and gain an identity, and Cuttack became the center of culture and changing attitudes towards dance. The arts training center Kala Vikash Kendra which began in 1952 and was supported by

Babulal Doshi, became a critical center for the codification of Odissi dance and music training, and all the big names of Odissi associated with it at one time. Interestingly, among the first three students of the Kendra were Sadhona Bose (who danced in

Raj Nartaki and other films) and her cousin Basanti Bose. For the first ten years, the institution taught Bharatanatyam, Manipuri, Kathak, and Odishan folk dances in addition to the few Odissi items. Gradually other institutions opened or began training in dance, such as the National Music Association of Cuttack.

In the early and mid 1950s, the dance form began to be known outside of Odisha particularly through the performances of Priyambada Mohanty and Sanjukta Mishra/Panigrahi in New Delhi and Calcutta which attracted the attention of the dance community most of whom had never seen the style before. But Odissi was not fully formed yet and performances were at most 15 minutes in length.

Priyamabada Mohanty in Mahari-style costume - Source: [16]

Left: 1956 Inter-University Youth Festival, Right: 1955

The late 1950s and 1960s saw Odissi expanded and codified into its modern format.

Kalicharan Pattanayak, after dismantling his Orissa Theatres, became instrumental in researching Odissi history's connections to the Natyashastra and presented his findings at the 1958 All-India Dance Seminar in New Delhi where Jayanti Ghosh demonstrated Odissi dance--a historic event for the dance form! (Also, the coining of the term "Odissi" for the dance is largely attributed to Pattanayak in in the mid-1950s.) With the benefit of Sanjukta Panigrahi and Mayadhar Raut's studies at Kalakshetra, the

Jayantika project was formed by gurus and scholars who set out solely to codify an agreed-upon Odissi dance style. The dance was refined and sanskritized and the costume and jewelry standardized. The "puspa chuda" style of arranging the hair in a bun surrounded by the pith circle and tahia was designed in 1959, and the distinctive silver bengapatia belt was first donned by Sanjukta in 1963. For some time the dance struggled to gain recognition as it was initially considered at best a variation of Bharatanatyam and at worst a poor imitation of it (supposedly the words of Rukimini Devi!). Indrani Rehman's learning of the dance form from Guru Debaprasad Das and her subsequent international tours took Odissi dance far and wide.

The connection of Odissi dance with the

Mahari temple dancers is controversial. It seems generally acknowledged that Odissi dance as we know it today was largely taken from the Gotipua tradition. Some claim that what was left of the Mahari's dance in the 1940s and 50s was so disintegrated that reconstruction could not done. But Anurima Banerji suggests another angle, writing, "Although the maharis who had kept Odissi alive underground were still accessible, they were deliberately excluded and distanced in this process, as they bore the stigma of prostitution and became associated with the degradation of culture. The effort to classicize Odissi was very much tied to purifying it of an explicitly erotic history, to ensure its lasting appeal to the elite and to seal its status as an authentic symbol of nationhood." Anurima also notes that unlike the "large body of scholarship on this history of the devadasi's metamorphosis into the prostitute, predominantly focusing on South India,""there is comparatively little scholarship on the specific status of maharis in Orissa [in] the colonial period."

![]() |

| Modern "Mahari" dancer |

In Odisha today, Gotipua and Mahari dances are still being performed as well as Odissi. Gotipua troupes have been given more

patronage and dedicated festivals in recent years. Comparing Gotipua dance to Odissi,

Ramli Ibrahim notes, "the movements are the same but the style and approach is different. Of course, there are also acrobatic movements derived from yoga, as well as tribal and folk movements [in Gotipua dance]," and the Gotipua dance is "very raw and exuberant" and does not have the "refinement or sophistication of the contemporary odissi." And then there are those women who are performing and trying to revive the dance of the Maharis.

Rupashree Mohapatra operates the only Mahari dance school in Odisha and operates an annual "Mahari Festival", and the Guru Pankaj Charan Odissi Research Foundation

gives out a "Mahari Award," Isn't it interesting how different each region of India is in the way its various streams of dance interacted, strengthened or faded away as the single classical dance forms were reconstructed in the 1930s-60s!

Due to differences that arose from the four main Odissi gurus, Odissi has at least four distinct styles today with some significant variation, one associated with each founding guru, and some scholars suggest Surendranath Jena and Nrityagram as fifth and sixth styles

1,15. It is Kelucharan Mohapatra's style that has unquestionably predominated to this day.

Film Connections

Something that most writings about Odissi dance history leave out are the connections the prominent names had with cinema in Odisha. The artistically-rich backgrounds of these individuals surely shaped the presentation and inclusion of dance in Odia cinema right from the very first production.

![]() |

| Mohan Sundar Dev Goswami |

The "father of Odia cinema" who produced the

first Odia film, Sita Bibaha, in 1936 against financial struggle and little Odishan infrastructure was none other than

Mohan Sundardev Goswami, who as mentioned above headed a popular Ras Leela group (and also later taught dance to Odissi Guru Mayadhar Raut in a short-lived Annapurna Theater C offshoot). Not surprisingly, the film is

said to have had "carefully chosen" settings for the dances and the songs which were written partly by Goswami. Unfortunately, the print is

said to be lost. Sadly, Goswami died in 1948, and had he lived longer he surely would have continued to make an impact on Odishan cinema and arts.

While

Kali Charan Pattanayak (Pattnaik) is best remembered for his scholarly contributions to the recognition of Odissi as a classical dance form, he was also involved in Odishan cinema.

Odiamoviedatabase credits him as the sole musician for

Lalita (1949) and as one of the lyricists for

Rolls 28 (1951),

Kedar Gouri (1954),

Jayadev (1987),

Krushna Sudama (1978), and

Sakshi Gopinath (1978). His one and only film appearance was a role in

Naari (1963) which also had

Durlab Singh (influential composer in theater dance) in the cast. Another scholar,

Lokanath Mishra, was part of the Jayantika project and was likely the same Lokanatha Mishra who was in the cast of

Lalita (1949).

Babulal Doshi, who as noted above supported the Kala Vikash Kendra institution, produced a number of Odia films that no doubt benefited from his love of Odishan arts. Among his productions were

Arundathi (about a dancer and filled with dance numbers),

Adina Megha (said to contain dances),.

Amada Bata, and

Matira Manish.

And last but not least, many

eminent Odissi dancers (notably Sanjukta Panigrahi, Minati Mishra, and Sangeeta Das) and

gurus (notably Kelucharan Mohapatra) performed and composed Odissi (and some folk) numbers in Odia films. These performances provide us priceless visual archives of the dance form at that time as it was reflected in cinema.

Unfortunately, after reading example after example of these dances and embarking upon my research with excited anticipation, I ended up finding

very few video examples to put in this post. But I know there are more out there! The

Lalita dance at the beginning of the post? It has a TarangTV logo in the corner and was clearly recorded from a TV broadcast which means the print of the film is out there, digitized, and is probably occasionally shown on TarangTV! If only they would publish their schedule online I could watch their online streaming service through YuppTV.

Lalita is also part of

a group of films that were screened by film enthusiasts in Odisha a couple years ago, so there are in existence prints of quite a few old classics. And looking at old Odia songs on YouTube, most of them have VCD branding in the corners but I've been unsuccessful at finding any of these VCDs for sale online. I wish I could fly to Odisha and peruse the VCD shops!

Here is a list of all the Odia films which are said to contain Odissi dances or folk dances by eminent Odissi dancers with Kelucharan's dances and choreographies grouped separately.

Film Choreographies of Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra

Among the core architects of modern Odissi, most were exposed to cinema in their youth. Mayadhar Raut as a child had run away to Bombay in an unsuccessful attempt to join films, and Pankaj Charan Das used to sell items outside of cinemas and would imitate the dance numbers for his friends. Kelucharan Mohapatra was no exception. He was a member of Goswami's Ras troupe and watched his maiden film

Sita Bibaha. Kelucharan had intensive compositional training around 1947 in the Uday Shankar style under Dayal Sharana who had studied at the Almora center, and when Shankar's dance film

Kalpana released Kelucharan watched it 40 times!

Kelucharan had the most extensive, known involvement with cinema and choreographed Odissi (and some folk numbers) for at least twelve Odia and Bengali films starting from his Jayantika days in 1958 through the 1980s. Writes Illeana Citaristi (whose book served as the source for most of this section), "During the shooting of these films, Kelucharan did not just give instructions regarding the execution of the choreography but followed every detail concerning camera position, angle, editing process and sound recording." Kelucharan's wife Laxmipriya also acted in quite a few films, though dancing is never mentioned.

![]() Maa (or "Ma," Odia 1958

Maa (or "Ma," Odia 1958, prod: Gour Ghosh) - This was Kelucharan's first composition for films, and he composed a Kela Keluni folk dance with two Bengali dancers. His wife Laxmipriya was the film's heroine! The image I've listed is not from the film but is a photo of Kelucharan performing the Kela Keluni dance with his wife Laxmipriya and Jayanti Ghosh—I love Kelucharan's smile. Starting in 1957, the Kala Vikash Kendra, aided by funding from the central Sangeet Natak Akademi, sponsored trips to the tribal areas of Odisha to study and record the tribal and folk dances of Orissa of which Kela Keluni was a part.

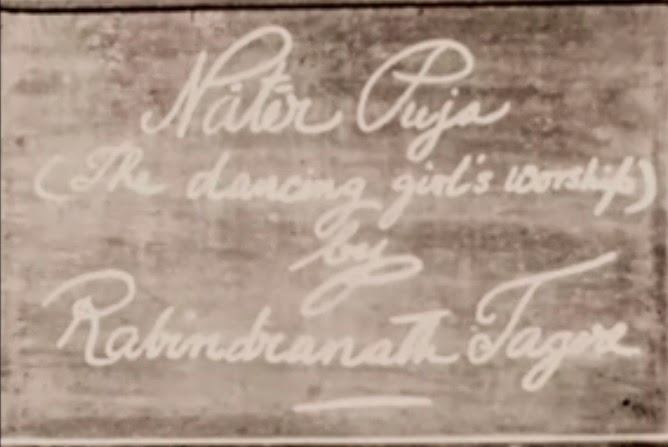

Mahalakshmi Puja (or "Shree Shree Mahalaxmi Puja," 1959, prod: Krushna Chandra Tripathy) - Kelucharan's second foray into film choreography, he composed a Dashavatara dance composed on screen for Sanjukta Panigrahi and Jayanti [Ghosh]. It must have been the same as the famous 1947 Dashavatar number that Kelucharan and Laxmipriya performed in Annapurna Theaters (and pictured earlier in this post). The dance is said to have remained practically the same even today, so it would be fascinating to compare. But most fascinating of all would be seeing the recorded moving image in 1959 of Sanjukta and Jayanti who were both important figures in Odissi dance.

Manika Jodi (1964) - Kelucharan choreographed a folk number that was performed by Guru Mayadhar Rout (one of the four architects of Odissi dance) and Urvashi Joshi.

Nirjana Saikate (1963, Bengali, Dir: Tapan Sinha) - I am so thrilled to have found the song below—

this dance has never been seen before on this blog! The dancer is Minati Mishra who was among the first batch of girls who started learning Odissi, and she is performing a Kalyani Pallavi choreographed by Kelucharan Mohapatra for the film. It's an interesting visual record of Odissi almost 10 years before it was documented in the

Films Division production Odissi Dance. This is the only Bengali film on the list, but the dance is presented so authentically it had to be included. While Illeana claims in her book that director Tapan Sinha asked Kelucharan to direct the dance after Tapan saw the dance rehearsals of Kelu and Minati for

Arundhati,

Arundhati was released four years after

Nirjana Saikate! The relatively static and elevated way the dance is filmed reminds me a lot of

Roshan Kumari's Kathak dance as captured by Satyajit Ray in

Jalsaghar.

Start :17

Arundhati (1967/8) - I posted about these dances previously, but I didn't know until my research for this post that the exquisite dances by a 30-year-old Minati Mishra were all composed by Kelucharan Mohapatra! This national award-winning film is an example of a "dance film" in Odisha because its plot surrounds a woman, Arundhati (Minati), who belongs to an Odissi dance troupe that tours the country.

"Namami Bighnaraj" - Minati Mishra performs on a small stage with musicians perched on each side. On the wall behind her is the iconic image of the chariot wheel as seen on the famous Konark Sun Temple. The first half of the dance is slow paced and statuesque, and the second half of the dance increases speed to show off some nice pure dance to the spoken rhythmic syllables.

"Debhika Para Aasare" - This creatively-choreographed group dance begins with the dancers entering the stage in a stylized walk and salutation, both elements of the introductory piece in Odissi, the

Mangalacharan or Ganesh Vandana. The raised and angled camera position highlights the formations of the dancers. Based on the plot description, the man who runs up to the stage at the end then proclaims his love for her much to her surprise and much to the shock of her boyfriend.

"Abhimanini" or "Mana Teji Aaji Saaje Maanini"- Minati Mishra also learned Bharatanatyam in addition to Odissi, and this number shows off her skills in both forms though Bharatanatyam heavily predominates after the 1:32 mark. Kelucharan composed all the dances in the film, so I imagine for this number he and Minati worked closely together to design the beautiful choreography. Minati is such a talented dancer with great form. The ending portion where she dances down her stair descent is thrilling! This song remains one of my most favorite film dances in Indian cinema.

"Shyama Gale Madhupure" - I have no doubts that Kelucharan also composed this folk number given his exposure to folk and tribal dances throughout his life and their being part of theater dance presentations and the early years of Kala Vikash Kendra. The way the group splits and interacts with one another is nicely designed.

Krushna Sudama (1976) - Kelucharan composed an Odissi group dance.

Tai Poi (or "Ta Poi," 1977) - Kelucharan choreographed a folk dance for this film. Might it be

this one?

Sri Krishna Rasa Leela (1979, prod: Komal Lochana Mohanty) - Kelucharan and chief assistant choreographer Gangadhar Pradhan (well known Odissi guru) composed group Odissi dances for this film.

Ramayana (1980) - "Dia Dia Mangala Hula Huli He Rama Hoibe Rajaa" - I am generally not a fan of the often tacky dances seen in mythological films from the 1960s onward, but this group dance in

Ramayana is delightful because Odissi-inspired movements are ingeniously woven into it.

Odiamoviedatabase credits Kelucharan as the choreographer (and I trust their credits given that they give the source, in this case the book "Odia Chalachitra Ra Agyat Adhyaya" by Bhim Singh). In the song, the seated king the women dance for is played by Uttam Mohanty who

seems to have been as popular to Odia cinema as MGR and NTR were to Tamil and Telugu cinema. I am not very knowledgeable about the innovations Kelucharan brought to Odissi in his usage of space and patterns, but I imagine this dance showcases some of his creativity.

![]()

Jayadev (1987, prod: Sachikanta Rout)

- Contains an Ashtapadi dance choreographed by Kelucharan. One of the songs in the film is "Rati Sukha Sare" of which there

is video of him performing outside of film on the stage and which may have been his original composition. Film image from

odiamoviedatabase.

Boitha Bandana (Unknown) - Kelucharan choreographed a Geeta Natya dance. I am unable to find any identifying information for the film.

Other Odissi Dances in Odia Cinema![]()

- Sri Jagannath (1950) - This film established debutante Gloria Mohanty "as a leading actress who was quite adept in dancing, acting and horse riding." Given that Gloria learned Odissi under Kelucharan Mohapatra, I imagine she danced "Odissi" in the film though the dance director is unknown. Gloria was a prolific stage actress who was introduced to theater by Kalicharan Pattnaik, and she acted in many Odian films including many noted in this post (Srjan).

- Kedar Gouri (1954) - Given that both Sanyukta (Sanjukta) Panigrahi and Gloria Mohanty are listed in the cast, it is assumed that at least Sanjukta danced and perhaps the two danced together! While the dance director is unknown, there's a good possibility it was Kelucharan.

- Matira Manisha (1966) - Produced by Babulal Doshi and directed by Mrinal Sen, this film is said to have featured a 10-year-old Aloka Kanungo before she learned Odissi from Kelucharan Mohapatra; perhaps she was just a child actress, but might she have performed a dance?

- Adina Megha (1970) - Produced by Babulal Joshi, this film credits Guru Ramani Ranjan Jena as the dance director.

- Sansar (1973) - Guru Ramani Ranjan Jena was the dance director. This is among the films screened in Odisha today so I know there's a copy somewhere!

- Kanakalata (1974) - Guru Ramani Ranjan Jena was the dance director.

- Sesa Sravana (or Sesha Srabhana, 1976) - Guru Ramani Ranjan Jena was the dance director

- Priyatama (1978) - Gangadhar Pradhan was the choreographer.

- Chhamana Athaguntha (1986) - Guru Ramani Ranjan Jena was the dance director.

- Baje Bainshi Nache Ghungura (1986) - The Hindu claims that Sangeeta Dash performed Odissi dance in the film, and odiamoviedatabase confirms her in the cast. I had posted previously that Kelucharan directed the film but I'm not able to find any mention of his film or dance direction in any of my sources. Sangeeta Dash was a talented Odissi dancer born in the 1960s who learned under Guru Deba Prasad Das in his unique style.

- Badhu Nirupama (1987) - Sangeeta Das was in the cast and likely performed a dance.

Odissi Dance in Recent Odia Films

So how does Odissi dance fare in Odia cinema today? Of the examples I found below, none are impressive. I find the filmi music and exaggerated emoting at odds with the graceful movements inspired directly from Odissi! I can't stop watching the dances to see how the Odissi choreography is utilized, but ultimately they are fluffy numbers that don't invite a repeat watch! I'm sure there are others in recent films that I'm not aware of. Anyone have other suggestions?

Akase Ki Ranga Lagila (2009) - "Kanhei Kanhei"- Archita Sahu, an Odia actress and Odissi dancer, performs an Odissi dance in the film in a setting of artistically lit dance sculptures. The emoting is filmy and the choreography is not pure Odissi, but Sahu's grace makes for a decent number. Certainly something you would not see in other-language films in India!

- "Saathire" - Archita Sahu danced again in last year's film

Thukul which

portrayed the romantic struggles of an Odissi dancer Tithi (Sahu) and a singer, and as you can imagine it contained lots of Odissi dance in multiple songs, practice scenes, and even over the introductory credits. But the group dances are presented in a filmy-pop way—the sets are gaudy, the music has a retro synth flavor, and the Odissi dancers look completely out of place. The choreographer of the film was the talented Odissi dancer Meera Das. Don't miss the part where the dancer drags herself in misery in a shallow pool of water! I have a feeling the songs in

Thukul are just what we can expect of Shilpa Shetty's "Odissi" in the unreleased film

The Desire: Journey of a Woman.

Thukul (2012) - "Gacharu Jhadile Patra" - Wow, the choreography of the men in this cheesy song is bad! The Odissi dancers appear at :24 and I have no idea why they are included in the song. Hard to sit through this one!

An interesting film

said to be in the works is "Kalpana," an Odia movie to be based on Odissi dance and helmed by Odissi dancer Saswat Joshi. But considering the false rumors of Joshi teaching Deepika Padukone Odissi for Sanjay Leela Bhansali's recently released film

Ram Leela, until

Kalpana releases I won't get my hopes up.

A Final Plea...and Coming Up Next!

Again, if anyone knows where any of the above films might be found, please let me know! Such rich treasures in the history of Odissi dance deserve to be brought to light. Coming up soon, I plan to post about Odissi dances in non-Odia films including a new one I recently discovered that is delightful!

Sources - Banerji, Anurima. Odissi Dance: Paratopic Performances of Gender, State, and Nation. PhD Diss.

- Chakra, Shyamhari. "Odia Cinema at Seventy-Five". Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas.

- Coorlawala, Uttara Asha. "Review: The Classical Traditions of Odissi and Manipuri." Dance Chronicle. 1993.

- Chatterjee, Ananya. "Contestations: Constructing a Historical Narrative for Odissi." Rethinking Dance History: A Reader. 2004.

- Chhotaray, Sharmila. "Narratives of Regional Identity: Revisiting Modern Oriya Theatre from 1880-1980." Lokaratna.

- Citaristi, Ileana. The Making of a Guru: Kelucharan Mohapatra His Life and Times. 2001. (peppered with cinema connections culminating in a detailed list on pages 144-146 of all the films Kelucharan choreographed for!)

- Dennen, David. "The Naming of 'Odissi': Changing Conceptions of Music in Odisha." Ravenshaw Journal of Literary and Cultural Studies. 2013. (draft can be read here).

- Evergreen State College Odissi Dance website

- Gauhar, Ranjana. Odissi: The Dance Divine. 2007.

- Gour, Santosh. "Odia Cinema and Odias in Cinema." Directorate of Film Festivals website.

- Kala Vikash Kendra website.

- Khokar, Ashish Mohan. "Guru Pankaj Charan Das: Fountainhead of Odissi." Narthaki.com

- Khokar, Ashish Mohan. "Guru Mayadhar Raut." Narthaki.com

- Khokar, Ashish Mohan. "Guru Deba Prasad Das: Guru of Global Odissi." Narthaki.com

- Lopez y Royo, Alessandra. "Guru Surendranath Jena: Subverting the Reconstituted the Odissi Canon."Dance Matters: Performing India. 2010.

- Mohanty Hejmadi, Priyambada and Ahalya Hejmadi Patnaik. Odissi: An Indian Classical Dance Form. 2007.

- Odiamoviedatabase.wordpress.com (I trust their credits given that they usually state the source of the information, often Odia Chalachitra Ra Agyat Adhyaya by Bhim Singh)

- Roy, Ratna. Neo Classical Odissi Dance. 2009.

- Sikand, Nandini. "Beyond Tradition: The Practice of Sadhana in Odissi Dance." Journal of Dance and Somatic Practices. 2012.

- Srjan - Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra Odissi Nrityabasa, including page on Guru Ramani Ranjan Jena and article "Odissi Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra" at Narthaki.com

- Varley, Julia. "Sanjukta Panigrahi: Dancer for the Gods." New Theatre Quarterly. 1998.

- Venkataraman, Leela and Avinash Pasricha. Indian Classical Dance: Tradition in Transition. 2002.

(Note: I did not make many specific references in this post other than for direct quotes because they would overwhelm the text and often were gathered and cross checked from multiple sources. If anyone is interested in where I got a certain piece of information, please contact me and I'm happy to provide the specific reference.)

Related Posts

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

+(36).jpg)

+(23).jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)